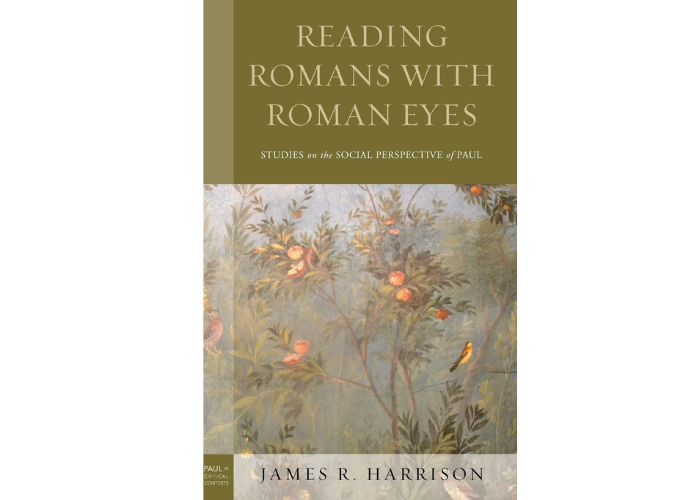

Prof. Harrison publishes his fourth monograph with Lexington Book/Fortress Academic Press

29 September 2020

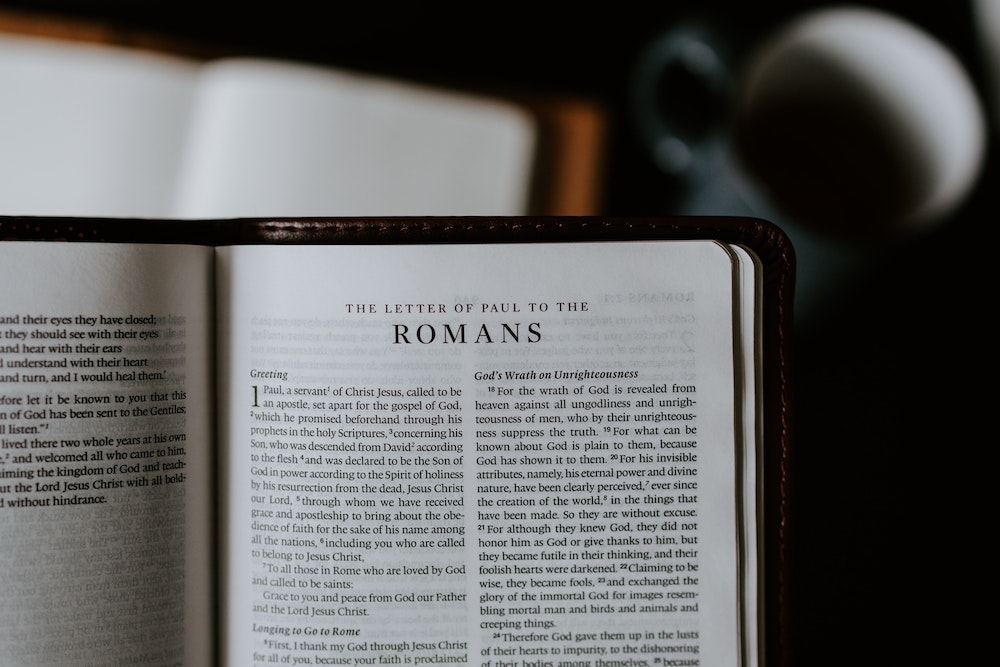

James R. Harrison, Reading Romans with Roman Eyes: Studies on the Social Perspective of Paul

Paul in Critical Contexts Series (Lexington Books /Fortress Academic Press, 2020), 433 pp.

This year Professor James R, Harrison, FAHA, Research Director of the Sydney College of Divinity, has just published his fourth monograph with Lexington Book /Fortress Academic Press. It is a study in reception history, exploring how Paul’s letter to the Romans would have been understood by its Roman auditors in their mid-fifties context of Neronian Rome. The book also poses the important question whether Paul’s engagement with the motifs of the imperial world and Roman culture generally in the epistle was an intentional strategy on the apostle’s part or whether he had just adopted a ‘broad brush stroke’ response in writing, hoping pastorally for the best result given that he was not the founder of the house churches in the city. The fact had Paul had never visited Rome at the time of the letter’s composition and therefore would know, it could be argued, very little about the capital and its inhabitants might well point in the latter direction.

However, Harrison argues that Paul would have known intimately what Roman culture was like from the Roman colonies he had visited and extensively pastored in through the Greek East and in Asia Minor (e.g. Pisidian Antioch, Philippi, Corinth), as well via co-workers such has Aquila and Priscilla who were Roman residents and who had ministered with him before he wrote the letter, and also via regular visitors from Rome that he would have met in the Roman East (e.g. businessmen, tradesmen, among others). It seems more likely that Paul would have intentionally presented the gospel of Christ crucified in the epistle with two vistas in view.

First, the apostle wanted to help his Gentile auditors to understand how they, by God’s justifying grace, had been grafted into the vine of Israel and how they were equal partakers of Christ’s righteousness with believing Jews. Second, the apostle also desired that Roman believers comprehend how they could live as transformed children of God through the newness of Christ’s Spirit in the city where the Roman ‘Son of God’, the emperor, lived and where the Roman values of ancestral glory, boasting, subjugation of the barbarians, and self-serving social relations were all dominant. Paul presents living out the resurrection life in the Body of Christ for the sake of others as the only alternative to plunging towards death and judgement in the Neronian ‘Body of State’ in the service of self.

The unique aspect of Harrison’s book is its extremely wide selection of contemporary documentary (inscriptions) and material evidence (archaeology, coins, iconography) from the Julio-Claudian city of Rome, in addition to the Roman literature (Tacitus, Suetonius, Dio, the imperial poets, Valerius Maximus, among others). These are employed as the backdrop against which we should asses Paul’s message, along with the bedrock of the Jewish scriptures undergirding his gospel. Romans, therefore, represents an exquisite conversation between two traditions: the blinding light of the revelation of God’s Messiah in Christ in the Jewish Scriptures, and the enslaving darkness of the idolatry of Roman power and culture in the capital and the Empire more widely.

The book, comprising ten chapters, republishes four essays of Harrison in revised form that have appeared before in print (Chapters 4, 5, 7, and 9). However, Chapters 2, 3, 6, and 8 are new, along with the introduction and conclusion. Themes which are addressed in the book are as follows: understanding the epistle to the Romans against the backdrop of the material remains of the city; the social constituency of the Roman church at Rome and its importance for Paul’s inversion of social and moral status at Rome; Paul’s indebtedness to the foolish barbarians (Rom 1:14) against the backdrop of Roman subjugation of the barbarians; the Neronian culture of “death” at Rome against the backdrop of Romans 5:12-21; Paul’s understanding of a groaning creation (Rom 8:18-25) within the Neronian “garden-city” and the visual evidence of nature in Livia’s villa; the social vision of Augustus’ Res Gestae at his mausoleum as opposed to the social vision of Romans; the Zionism of Paul (Rom 9:33; 11:26) in contrast to the Roman dismissal of Jewish culture and status; the Roman ideal of glory as opposed to Paul’s understanding of boasting in glory.

In sum, the legacy of Paul’s letter to the Romans would overturn the self-congratulatory and status-preoccupied culture of antiquity in the western intellectual tradition, replacing it with the humility of the dishonoured and crucified Christ, who was vindicated by God as the risen Lord of all. Harrison’s monograph helps us to see this profound cultural shift more clearly.